Today, I am going to talk about the K-movie, “The Handmaiden”.

“The Handmaiden” (Korean: 아가씨) is a South Korean erotic psychological thriller film directed by Park Chan-wook, released in 2016. The film is inspired by the novel “Fingersmith” by Sarah Waters, with the setting changed from Victorian-era Britain to Korea and Japan during the 1930s when Korea was under Japanese colonial rule. The movie’s plot revolves around a complex scheme involving identity theft, inheritance, and betrayal, featuring richly developed characters and unexpected twists. Here’s a look at the main cast and their roles:

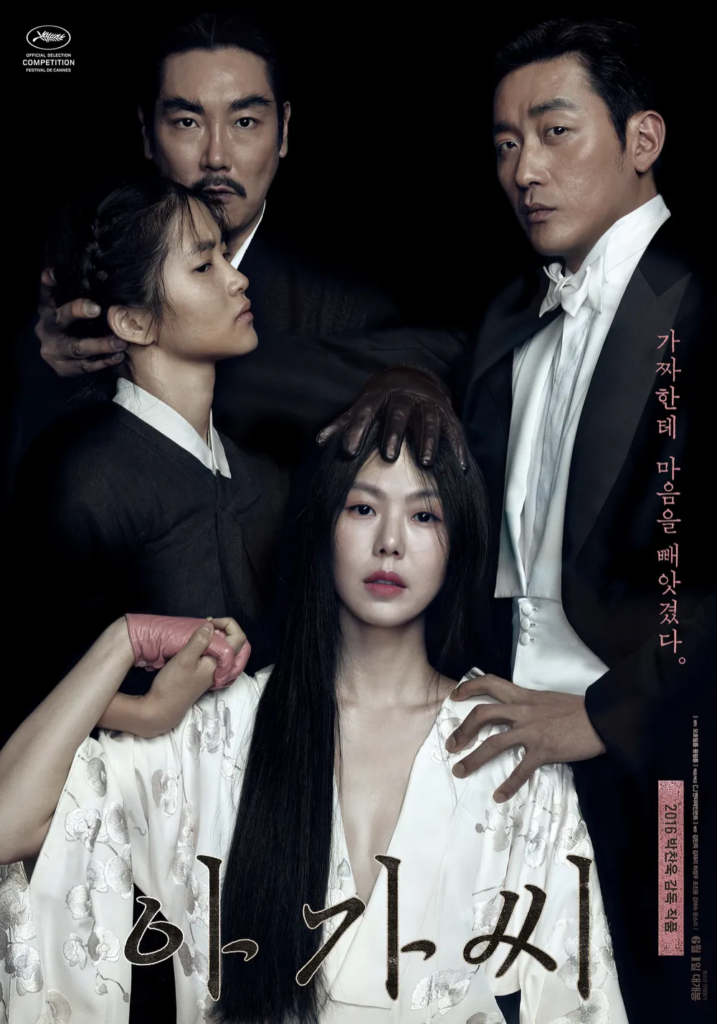

- Kim Min-hee plays Lady Hideko, a wealthy Japanese heiress living in a secluded estate. She becomes the target of a con to steal her inheritance. Her character is central to the unfolding narrative, revealing layers of complexity and depth as the story progresses.

- Kim Tae-ri plays Sook-hee, a young Korean woman hired as Lady Hideko’s handmaiden. However, Sook-hee harbors a secret; she is a pickpocket recruited by a con man to help him seduce Lady Hideko as part of his scheme to marry her and then commit her to an asylum to steal her wealth.

- Ha Jung-woo plays Count Fujiwara, a con artist posing as a Japanese nobleman. He orchestrates the plan to seduce and marry Lady Hideko, using Sook-hee as part of his scheme to secure Hideko’s fortune.

- Cho Jin-woong plays Uncle Kouzuki, a perverted book collector and the guardian of Lady Hideko. He is a key figure in the plot, as his control over Hideko’s life and fortune is what the con artists aim to exploit.

“The Handmaiden” is celebrated for its visual style, intricate plot, and the performances of its lead actors. It explores themes of freedom, sexuality, and the subversion of power dynamics, all while delivering a suspenseful and erotically charged narrative. The film received critical acclaim worldwide for its direction, screenplay, and aesthetic, becoming a standout work in Park Chan-wook’s filmography.

“The Handmaiden” Plot

In 1930s Korea, a conman known as Fujiwara Count plans to marry Lady Hideko, a plump Japanese heiress, to steal her fortune. His scheme involves imprisoning her in seclusion. To execute this plan, he seeks the help of Sook-hee, a young pickpocket from a den of thieves. Posing as a handmaiden, Sook-hee prepares for the count’s impending marriage to Lady Hideko. The eerie atmosphere of the secluded mansion radiates mystery and isolation.

As Sook-hee begins her mission, she finds herself drawn to Lady Hideko’s beauty and vulnerability. However, her initial loyalty to the count is challenged by the passion she develops for Lady Hideko. Meanwhile, Lady Hideko struggles with her uncle’s twisted obsession and battles against societal expectations and biases revealed through her uncle’s sadomasochistic literary pursuits.

The narrative unfolds through different perspectives, exposing retiree alliances and secrets. Shocking revelations overturn power dynamics, leading to unforeseen changes and evolving desires. The relationship between Sook-hee and Lady Hideko intensifies into a passionate and tumultuous love. Exploring themes of power, desire, and liberation, the film challenges societal morals and gender roles, seeking an escape from love, trust, and oppression.

The climax, marked by carefully planned twists, unveils the characters’ true intentions. Moments of piercing revelations, exposure, and profound transformations culminate in tense and emotionally charged resolutions. In the end, “The Handmaiden” asserts itself as a tale of deceit and desire, using the artifice of lies and the temporary power of filmmaking to establish its place. The film’s vibrant and focused plot, complex characters, and lavish cinematography weave a tapestry of deception and desire.

The conclusion sees characters breaking free from their individual constraints, forging new paths, and reclaiming agency in their lives, leaving observers with a cathartic experience. “The Handmaiden,” with director Park Chan-wook’s masterful direction and stellar performances, offers a visually stunning and intellectually stimulating cinematic journey.

“As The Handmaiden” hurtles towards its apocalyptic conclusion, a complex web of deceit, desire, and power play unfolds, leading to a series of shocking revelations and moments of transformation for the involved characters. When Lady Hideko and emotionally entangled Sook-hee dramatically expose their identities in the slums, the story takes unexpected turns, threatening Lady Hideko’s trust and the fragile bond between the two women. Fujiwara Count’s plan to usurp Lady Hideko’s wealth becomes increasingly intricate, manipulating the vulnerabilities of both women to enhance his control.

As the war of wits unfolds, the mansion, once a place of confinement and manipulation, transforms into a battlefield of wit and cunning. Layers of deception unravel, forcing each character to confront their truths and reckon with their provocations. Sook-hee and Lady Hideko, seemingly pawns in a grand game, assert their agency, astonishingly and powerfully challenging their assigned roles. The dynamic shifts from an imbalance of power to an unexpected collaboration rooted in indifference to authority.

The film’s climax is characterized by a meticulously planned escape, as the characters’ fates are ultimately decided. Moments of stabbing, exposure, and profound transformations drive the narrative towards its resolution. The final scenes explore the characters’ futures, as they embark on a journey of exploration and defiance against the impact of their participatory history.

In the end, “The Handmaiden” establishes itself as a tale of deception and liberation, woven together through the artifice of lies and the evidence of desire. The film’s conclusion, marked by the triumph of deceit, leaves an indelible mark on the observers, and its complexity and exposure echo long after the credits have rolled.

The film ‘The Handmaiden’ is distinctive for its three-part structure, alternating protagonists, and changing narrators to resolve the plot. Parts 1 and 2 introduce the same events from different perspectives, creating entirely different storylines, while Part 3 converges the narrative into a unified plot. The film evolves through the structural composition of the plot and alternating perspectives on events. Furthermore, the movie prominently explores violence directed at a particular gaze. Oppressive masculinity and the resulting sacrifices of women often stem from distorted perspectives. Regardless of the essence, the regulation through such a gaze constitutes a severe form of violence.

In this context, the symbolic use of a snake or octopus to represent Kouzuki seems fitting. The snake serves as a device revealing malicious and cruel traits, mirroring the appearance of male genitalia. The octopus, considering the painting depicting a woman engaging in sexual relations with an octopus mentioned in the reading group, aptly reveals a distorted view of femininity. While the film addresses the violence inherent in the gaze centered around both men and women, such violence manifests in various forms in our lives. Distorted perspectives contribute to violence, whether directed at individuals with disabilities, treating poor individuals as burdensome, spreading rumors about people based on limited observations, or stigmatizing overweight individuals as lazy and dirty.

It might not be easy for people to see others for who they truly are, as illustrated when Sook-hee first looks at Lady Hideko. However, is it not right to make an effort to understand others as they are, empathizing with their emotions and experiences? ‘The Handmaiden’ narrates the story of a woman escaping from violent and oppressive male dominance. The film contains numerous feminist elements, which might make some viewers uncomfortable. Moreover, the presence of homosexual themes and violent scenes may contribute to discomfort for certain audiences.

Review

The film “The Handmaiden” marks the return of the renowned South Korean director Park Chan-wook to the domestic film scene. This movie, competing in the prestigious Cannes Film Festival and earning recognition for its art director Ryu Seong-hee, is an adaptation of Sarah Waters’ novel “Fingersmith.” The storyline follows a pickpocket named Sook-hee, introduced by a conman to a noblewoman, Lady Hideko, living with her uncle. Sook-hee assumes the role of a maid, aiming to facilitate Lady Hideko’s marriage to the conman, after which they plan to send her to a mental institution and divide her inheritance.

The narrative unfolds in three parts, with the first part focusing on Sook-hee’s perspective, establishing the initial setting and creating subtle tension between characters. The film straddles the thriller and melodrama genres, with the second part shifting to Lady Hideko’s viewpoint, revealing previously unknown situations. The third part introduces further twists and ultimately leads to a grim fate for characters driven by malice.

The three-part structure is fundamental to the storyline, with Park Chan-wook choosing to explicitly label each part for the audience. This may serve to remind viewers of the cinematic nature of the film, reminiscent of Bergman’s “Persona” or the narration technique in “Autumn Sonata.” While the movie aims for a literary feel, possibly for artistic reasons or to facilitate viewer comprehension, it distinguishes itself from Park Chan-wook’s previous works.

Personally, the film evoked memories of Japanese pink films (romantic pornography) from the 1970s and 1980s. Although not directly produced within the same system, certain elements, such as posters and cinematography, brought to mind the aesthetics of pink films. Additionally, the film pays homage to European classic films in several scenes, drawing parallels with iconic works like “Gone with the Wind” and Luis Buñuel’s “Belle de Jour.”

While being a movie with twists, which might diminish interest upon knowing many details, the post-viewing reflection on “The Handmaiden” suggests that the poster effectively encapsulates the story and characters. The author expresses a preference for the poster of Park Chan-wook’s “Thirst,” but acknowledges that the poster for this film is also quite impressive, particularly in conveying information through the hands of the four characters.

“The Handmaiden” provides an enjoyable blend of story, character dynamics, unique comedy, and a chance to witness different facets of established actors like Kim Min-hee, Ha Jung-woo, and Cho Jin-woong. However, the most delightful discovery is the newcomer Kim Tae-ri, who impresses with her portrayal of a character starkly contrasting her innocent appearance. The author commends the cast’s ability to infuse various tones into the film, creating a well-rounded viewing experience.

Kim Min-hee, now a prominent figure among 30-something actresses, stands out alongside Bae Doo-na. Directors emphasizing storytelling are increasingly seeking her, and her recent collaboration with Hong Sang-soo and Isabelle Huppert at Cannes has sparked anticipation. Ha Jung-woo successfully revisits a comedic character, Cho Jin-woong tackles a challenging role with a powerful ending, and Park Chan-wook once again proves his directorial prowess, making “The Handmaiden” a highly anticipated and valuable addition to the Korean film industry.